By Robin Rowles

This essay discusses Mr Fowler’s tactics in rescuing his intended, Alice Rucastle, from the shuttered turret room in ‘The Copper Beeches’. Mr Fowler’s involvement and tactics are summarised in three sentences at the conclusion of the story. However, it is possible to paint a fuller picture of Mr Fowler’s plan, by thinking it through and applying a set of reasonable deductions. Mr Fowler’s goal was clear, but to deliver it, he had to deploy three tactics: observation, the gathering of intelligence, and patience. I will examine these in turn.

Observation :

No successful operation can succeed without knowledge about its target and Mr Fowler needed information about the house and household of the Copper Beeches. Therefore he stationed himself outside the house in the Southampton Road and observed. Being a nautical man, Mr Fowler would have had an eye for detail and noted the exterior layout of the house and gardens. It is not stated in the story if Mr Fowler was an officer in the Royal Navy, as Lieutenant Arthur Charpentier was in A Study in Scarlet, or a civilian officer like Captain Jack Croker in ‘The Abbey Grange’. What we do know is that Mr Fowler showed the determination of the former, and the ingenuity of the latter in developing his strategy. Mr Fowler had questions that needed answers: Where were the doors and windows? Where did the garden paths go? Did the architecture of the house lend itself to climbing the walls, if necessary? We may surmise with a degree of confidence that Mr Fowler made several dry runs, especially as the house had a fierce mastiff that roamed the grounds at night. Could Mr Fowler cross the lawn before the dog? This was a rather important question to be considered when planning a break-in and rescue attempt.

Intelligence :

Observing the exterior of the Copper Beeches was only one aspect of the overall strategy. If his plan was to succeed, Mr Fowler needed help from within the house. An ally, from whom he could obtain intelligence about the house’s internal layout, and the household’s daily routine.

When planning an invasion, whether military or peaceful, it is a good policy to befriend the locals, whose neutrality or loyalty can be swayed by convincing arguments.

Mr Fowler’s tactic here was to befriend the housekeeper, Mrs Toller, and persuade her, by ‘arguments metallic and otherwise’, that their interests were mutual. Within the story, we are not how Mr Fowler engaged with Mrs Toller or how their alliance developed; it is enough to know he succeeded. Mr Fowler would have learnt that Mrs Toller was the housekeeper and therefore dealt with cooking, cleaning and general housekeeping. Toller was the groom and also responsible for the family dog, Carlo. Significantly, Mr Fowler would have learnt that Toller was a heavy drinker and Mrs Toller disapproved of her employer’s treatment of Alice Rucastle. But Mr Fowler also needed information about the daily routine: For example, who locked up and when? What time of day was the dog released to roam the gardens?

Given that at the end of the adventure, Mrs Toller described herself as ‘Miss Alice’s friend’ and Mr Fowler as ‘a kindly spoken, free-handed young gentleman’, it’s reasonable to infer that little persuasion was needed. Thus, as Holmes summarised, Toller did not want for drink, the dog would be chained up on the evening in question, and a ladder would be left available.

It is often a trope of adventure fiction that whenever somebody breaks in to, or escapes from a building, there is always a ladder conveniently placed. With this simple line of dialogue, this trope is removed, and the ladder is transformed from a lazy plot device to a detail showing Mr Fowler’s foresight.

Patience :

Having scoped out the external and internal layout of the house, the household’s daily routine, and secured the assistance of Mrs Toller, Mr Fowler now had to exercise patience. He had made his preparations and now had to pick his moment to carry out his rescue. Mr Fowler knew he could not delay indefinitely, but also knew he would only have one chance. What was the best time of day? Daytime was almost certainly out of the question as the probability of being seen in open daylight was too high. The house was just off the Southampton Road and there would be passers-by.

Similarly, dead of night was too risky, as the sound of ladders being mounted and breaking in would be heard. The Copper Beeches was five miles from Winchester in open countryside. Unlike the bustle and hubbub of a city, the countryside is quiet. At night-time it is even more so. Apart from the hoot of an owl, or the rattle of a train, for instance, very few sounds break the veil of night. Sound carries and any suspicious noises around the house and gardens could easily rouse the household and invite investigation. A night attempt also requires the use of lights. Mr Fowler would have to ascend the ladder, in darkness, with one hand carrying a lamp. This was too risky a proposition.

The dawn raid is often a popular theme in thriller fiction, and this might have had several advantages. We can fairly safely assume Mr and Mrs Rucastle would be asleep. Mr Rucastle almost certainly. He was an older, corpulent man with an implied sedentary lifestyle. His constant scheming and his financial worries would have tired him, mentally and possibly physically. Mr Rucastle may have needed more sleep than a fitter, younger man, and it is likely he would have slept quite heavily. Of the servants, Mrs Toller may have been up and about as servants rise before their employers to attend to their morning duties. However, Mrs Toller was an ally of Mr Fowler and no threat to his mission. Plus, there was a good chance that Toller would be sleeping off an alcoholic binge. On the other hand, a dawn raid would entail waking Alice Rucastle, and this could use up precious time. Every minute’s delay increased the chance of discovery as the day lightened. There was another risk: we know that Mr Rucastle made regular visits to the turret room, either to browbeat his daughter into signing away her inheritance, or simply check his prisoner was secure. It is possible that Mr Rucastle made a point of awakening at dawn to check the turret room, before retiring back to bed to resume his sleep.

The best time for Mr Fowler’s mission was dusk. The Rucastles were out, ostensibly visiting friends, although Mr Rucastle was suspicious and set a trap. However, Mr Fowler was not wrong in his choice of timing. Dusk is when human energy and reflexes are arguably at their lowest. People whose circadian rhythms make them morning larks are fading, and night owls are just waking up. The transition from day to night offered the best odds on a successful rescue venture.

Meanwhile, Mr Fowler would have spent the time waiting for dusk to fall going over his plan, checking every detail. A line from Shakespeare’s Hamlet may have summarised his thoughts: ‘The readiness is all’.

Although Mr Fowler was planning a rescue, not revenge, his preparations had to be exact, as those who fail to prepare, usually prepare to fail. Was everything ready? The Rucastles had departed in their carriage, something he almost certainly learned via Mrs Toller. That cut down any potential interference with his operation.

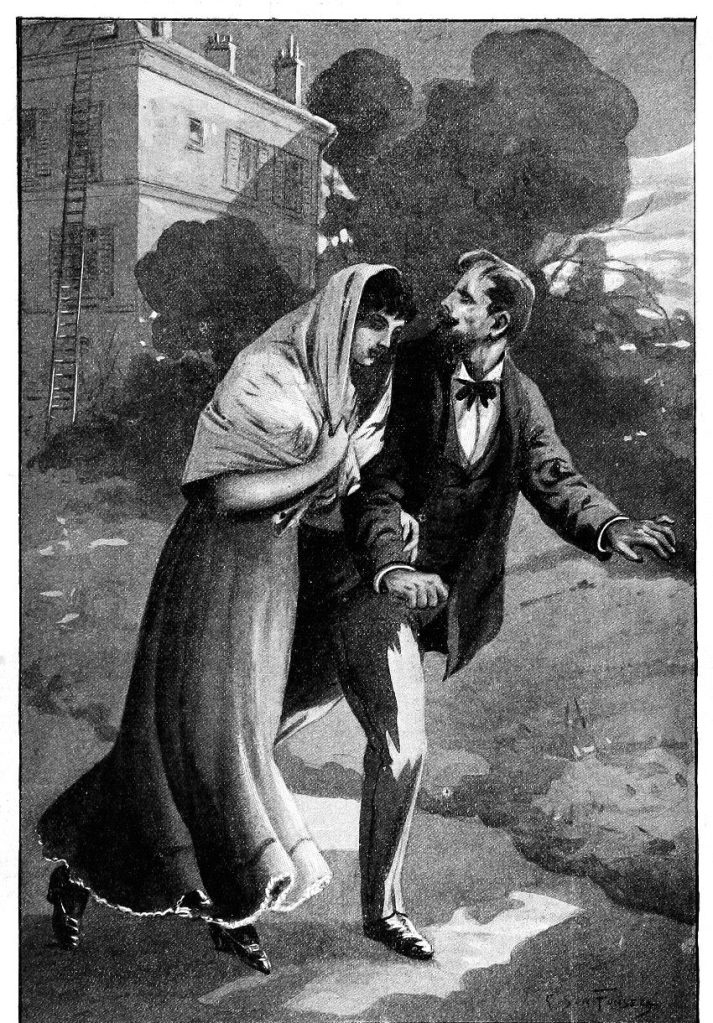

Toller drunk: check. He didn’t know Miss Hunter had imprisoned Mrs Toller in the cellar, but this didn’t matter as Mrs Toller was on his side. The dog was chained: check. Finally, that all-important ladder was in place: check. Everything was in place, and it was time for action.

Conclusion:

The two rescue missions of Holmes and Watson on the one hand, and Mr Fowler on the other never meet in the story, although it’s a reasonable inference they didn’t miss each other by much. Mr Rucastle, being suspicious, had turned his carriage around and returned home. He arrived at the turret room almost on Holmes and Watson’s heels. Mr Rucastle was a schemer, and schemers, not being honest themselves, are often suspicious.

The gist of Mr Fowler’s plan was supplied by Mrs Toller in the story’s ‘wrap-up’, and Holmes succinctly summed up the key points. It’s almost a pity that in the original story, Holmes and Watson never met Mr Fowler, although this did happen in the Douglas Wilmer BBC television adaptation. This is important, as we see that Mr Fowler’s appearance matches his evident intelligence: he is smartly dressed and well-spoken. Therefore, we can see that Mr Fowler’s rescue of Alice Rucastle, was well planned, based on observation and intelligence, and perfectly executed thanks to that other essential requirement of any operation: patience, or picking the right moment.

Sources:

‘The Copper Beeches’, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, BBC TV episode, 1965, directed by Gareth Davies

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Adventure of the Copper Beeches’, The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, ed. Leslie S. Klinger, (New York/London, 2005), pp351-383