A Sherlock Holmes- Professor Challenger crossover

By Robin Rowles

The spring of the year 1896 was warm, placid and peaceful. The weather had recovered from its rainy spell earlier in the year and there was every hope for a glorious summer. Then the explosions began. Sherlock Holmes was faced with an investigation that might have originated from the pen of HG Wells, whose scientific romances fired the imagination. Indeed, when the facts were recounted to Wells, he immediately saw the dramatic possibilities and wanted to write the remarkable story behind the man who found a way to walk through walls.

I was part of this investigation, so I am telling the story. However, Wells ‘borrowed’ one element of the mystery, and instead of writing about a scientist who discovered a way of displacing solid matter, wrote a story about another, fictional, scientist, who discovered a way of defying gravity itself. Although naturally disappointed, Wells promised not to allude to the real story, even indirectly, in case it encouraged reckless experimentation.

I am only writing this now under the stern gaze of Professor Challenger who requires a detailed record of the facts. Like Sherlock Holmes, Challenger was intolerant of what he called unnecessary romance and wanted a straightforward account. However, my readers would find this as engrossing as an out-of-date copy of Bradshaw, and Challenger reluctantly acceded to my request to breath more life into the narrative, provided that certain facts and one very specific formula, were either removed, redacted, or altered. However, I am getting ahead of myself.

April 1896 started brightly, and Sherlock Holmes was rather busy. It was just before Easter, and Holmes and I, feeling somewhat jaded, were looking forward to a little rest. This was not to be. A tap at our door, and Billy entered.

‘Mr Holmes, inspector Lestrade’s here’ he chirped, looking rather pleased as though he’d said something clever. Holmes sat up in his armchair and emerged from behind the pages of the Daily Telegraph.

‘Well, that’s nothing new. What’s up this time?’ Holmes asked.

‘Dunno, Mr Holmes. Except he’s brought a giant with him.’

Holmes was about to ask who this giant was when he walked into the room. I say walked, but it would be more correct to say he strode in. The whole room shook, and the coalscuttle rattled in protest at this titan’s intrusion. We had entertained larger than life characters in Baker Street before. Sherlock Holmes’ brother, Mycroft was formidable in size and intellect, and the murderous Dr Grimsby Roylott had twisted our poker as though he was practicing origami.

The vengeful but justified Dr Leon Sterndale was a force to be reckoned with, but our visitor eclipsed each of them.

There was no doubting who he was. A regular, if controversial speaker at the Royal Society lectures and frequent contributor to the letters page of the Times with suggestions to the government on all scientific matters. From the elimination of the common housefly to preventing tidal floods in the river Thames, there wasn’t a single topic our visitor didn’t have an opinion on. I refer, of course, to Professor George Edward Challenger. Lestrade scuttled in after the professor and literally stood in his shadow, nervously holding his hat and stick. Billy deftly relieved Lestrade of these items and he subsided onto the settee. Meanwhile, our other guest maintained his stance. The somewhat cluttered sitting room in 221b suddenly felt somewhat claustrophobic.

Challenger spoke first. ‘Good morning, gentlemen. I presume you are not busy’ he said as he plonked himself into the guest armchair. Holmes recovered his wits.

‘Good morning, Professor. Please let me have the facts, in due order.’ Challenger harrumphed. ‘Lestrade has all the details. I came here to tell you you’re going to take the case’.

Holmes smiled. ‘What case, Professor? You haven’t told me anything yet’. Challenger turned to Lestrade. ‘Well, man, get on with it. We haven’t got all day.’ Lestrade reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a notebook. ‘Explosion at the faculty of science and technology, Imperial College last week. April 1st, to be precise. Nothing of significance- ‘. Here Challenger interjected ‘Nothing of significance, except months of scientific experiment and research lost.’ He growled. Lestrade saw his chance and continued ‘-and ever since then, we’ve had reports of people walking through walls. Not ghosts, Mr Holmes, but real flesh and blood’. To say that Holmes and I were rocked back on our heels by this statement wasn’t quite true. The Baskerville affair and that of the Sussex Vampire had demonstrated there was usually a logical explanation for everything. However, this was a new departure. Holmes sat up in his chair, all tiredness gone. ‘That’s quite remarkable’ he proffered the obvious comment and added ‘every criminal in London would rather know that trick’. Challenger glared.

‘No trick, Mr Holmes. It’s happening now’. Shopkeepers are reporting people walking through walls, locked doors, closed windows. Banks are guarding their strong-rooms and everybody’s afraid of being burgled.’ Holmes held up a finger to quieten Challenger’s outburst. ‘But how did this come about?’ he asked. Challenger took a deep breath.

‘Come to the laboratories and I will show you’, he said. Half an hour later, we were shown into the office of Professor Sir James Smith. Sir James was Dean of the Faculty of Science and Technology. After introductions, Sir James wasted no time on small talk, but led Holmes and I down long white corridors. Here, we passed laboratories where fellows of the University toiled away at their experiments.

We reached a doorway, which was guarded by a Metropolitan police constable. He straightened up when he recognised Holmes. Sir James waved him away, unlocked the door and showed us the room behind. Or rather, showed us what was left of the room. It was a smallish storeroom with a small antechamber on the left-hand wall. The walls were ranged with wooden shelves and illumination was provided by a modern Edison and Swan electric lightbulb.

Further illumination was afforded via a large window overlooking the gardens, although the modernity of the lightbulb was offset by the wooden shutters that opened either side of the window. However, the room was a mess. The floor was a sea of smashed scientific instruments, shards of wood from the shelves and mangled pieces of equipment which Sir James explained were the remains of scientific experiments. The professor described the sequence of events.

‘It was just before nine o’clock and I was in my study finishing some paperwork’.

‘What was the exact time, Professor?’, Holmes asked.

‘Between five and three minutes to nine’. Sir James answered.

‘How do you know that?’ Holmes pressed his question.

‘Because the faculty bell had struck. It goes off every night at five to nine to remind those fellows in the laboratory to pack up. It’s also when lectures and seminars finish.’ Holmes asked the professor to continue.

‘There was a commotion in the corridor, and I popped my head out to see what was going on. Tovey, our commissionaire was following a man. He was wearing a lab coat and was carrying something, a Gladstone bag, I think’. Holmes’ eyes lit up.

‘Where did he go?’

‘He ran into this room and into this’, here the professor pointed to the smaller room ‘and locked himself in’. Then there was an explosion which wrecked this storeroom. By now, Tovey had caught up and showed great presence of mind by standing guard at the door until I arrived. We thought we had our man trapped in here where we store the research papers.’ Here, the professor turned sadly to Holmes and turning up his palms, gave a bemused shrug.

‘Where is this man now?’ Holmes asked. The professor took a couple of deep breaths then answered. ‘We don’t know Mr Holmes. He wasn’t here when Tovey unlocked the door to this store-room, nor the file-room’. Holmes turned and held his breath for a second or two.

‘So he escaped, then’. This was the only possible solution. ‘Could he have gone through the window?’

‘It doesn’t open Mr Holmes. It’s purely for illumination. There are air vents above and below that provide all the ventilation necessary. And he can’t be hiding unless he’s invisible. There’s nowhere to hide’. Holmes snorted. The professor turned and his eyes walked around the devastated store-room looking for an answer. Finally, he found one.

‘In which case, Mr Holmes, our mysterious visitor has achieved something very remarkable. He can only have escaped being captured by Tovey and myself’, he hesitated then went on with the only logical answer that fitted the utterly fantastic narrative. The professor took another deep breath. ‘Mr Holmes, he must have walked through the wall!’.

I was not surprised at Holmes’s response. Holmes often remarked that after eliminating the impossible, whatever remained, however improbable, must be the truth. I was there not surprised when Holmes calmly accepted Sir James’s idea that the intruder had transgressed the laws of physics and simply walked through a solid wall. However, it was the formidable figure of Challenger who scorned this theory. Sir James quickly excused himself and tried to pretend he wasn’t running away from an argument. Lestrade followed him on the pretext of collecting his notebook from Sir James’s office.

The debate sizzled throughout the half hour journey back to Baker Street, then rekindled into open argument in the sitting room. However, the verbal fight wasn’t between Sherlock Holmes and Challenger, it was between Mycroft Holmes and Challenger. Two physical giants with giant brains at loggerheads, truly a Clash of the Titans.

The row was interrupted by our housekeeper Mrs Hudson arriving with the tea-tray. The housekeeper instantly took in the scene, and handing me the tea-tray, proceeded to separate the antagonists, telling them to sit quietly, each at different ends of the Chesterfield sofa. Had the situation not been so serious, it might have been comical, Mycroft Holmes, who occasionally was the British Government, and Professor Challenger, the pioneer of science, sat like massive bookends. The springs of the old Chesterfield creaked in protest at their combined weight. Mrs Hudson poured the tea and thus restored peace and harmony to 221B Baker Street.

During this little interlude, Holmes had been verbally outlining points about the case, and I made a point of jotting these down. To my mind, there were several key questions. Assuming somebody had walked through the wall, how was it done? And what was the point of the explosion? And was the explosion cause or effect? So many questions. Holmes answered them without my asking, as usual.

‘To answer your questions, Watson, somebody did walk through the wall.’ At this point Challenger stirred and Mycroft half turned. The settee creaked ominously. Holmes raised a finger to quell the interruption that Challenger and Mycroft were brewing. After a few seconds, each subsided back into his corner, neither wishing to lose face. Holmes continued. ‘The trick was done by temporarily displacing the structure of the wall, down to the very particles of matter itself. ‘. Challenger muttered something about atoms and this time would not be suppressed. However, Holmes raised his index finger, which had the effect of silencing Challenger. Doubtless this had rarely happened before and would probably would never happen again. Holmes spoke. ‘I know what they’re called, Professor. Let’s keep things simple. Now, where was I? Ah yes. The explosion was both cause and after effect. You might say it opened the door and closed it again. The experiments were smashed to cover the fact that something was taken. It’s quite a well-known ruse among burglars. You have questions, Professor?’.

Holmes had seen Challenger’s cautious hand and I noted the scientist was waiting to be invited to speak. It was a temporary phenomenon but was the giant of science learning manners? Challenger gathered his thoughts then spoke. ‘But what was stolen then?’. Holmes leaned back in his chair and lit his pipe. Having achieved this goal, the detective spoke. That’s what Sir James will tell us, hopefully tomorrow. I left a note with Tovey, asking Sir James to make a complete inventory of everything in that room. It’ll take a few hours but if I’m right, we’ll hear about tea-time tomorrow night’. I smiled. Some people made wild guesses, others careful estimates, but Holmes’s predictions were uncannily accurate. ‘The lesser of two evils’, I proffered this observation. Holmes nodded.

‘Yes, poor Sir James will have to explain this to the Faculty Governors. It’s not the first time that experiments have come to grief’.

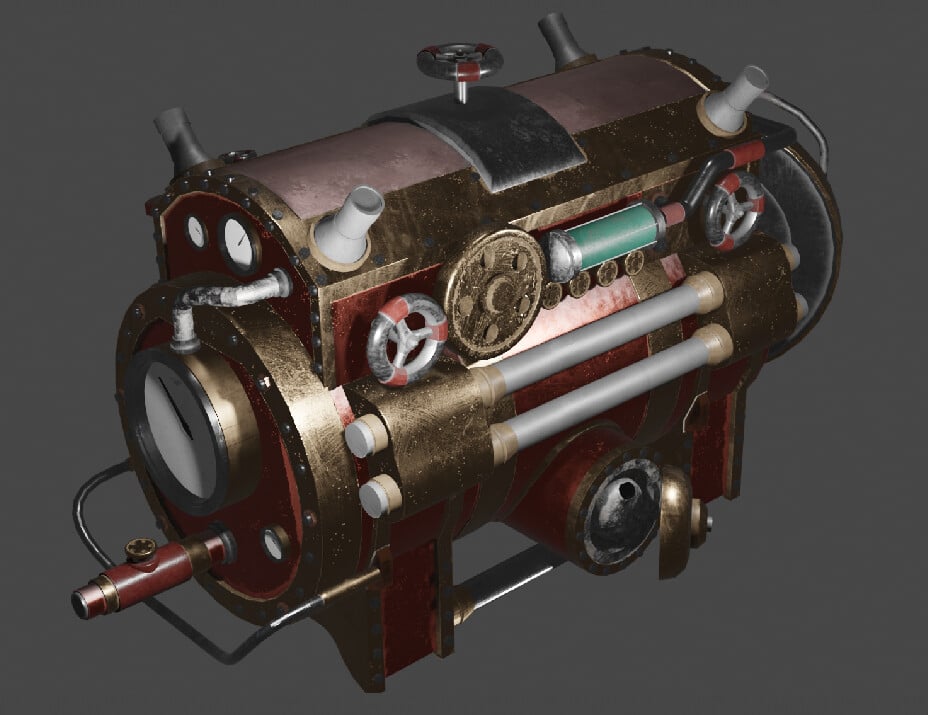

The next day brought fresh news in the form of Sir James who was bearing a small cardboard box. Over coffee, Sir James displayed its contents. It resembled a Swan and Edison electric light bulb, except there was a small hexagonal prism at the end. Challenger came in at that point and immediately started explaining its use. As far as I understand Challenger’s explanation, it was a focussing coil for a device he called a ‘Particle Dispersion Field’ generator, or PDF for short. To cut a wearisome explanation short, the device displaced particles of matter, creating an aperture. The explosion was the exchange of mass to kinetic energy into heat, then back to mass as the particle field collapsed and the atoms reunited in their original position. The field only lasted a few seconds, but this was sufficient to allow the operator of the device to pass through solid structures. Thus the mystery of walking through walls was solved. The question was, why? Holmes interjected.

‘If whoever has this device, how are they using it without the focussing coil?’. Sir James answered this. ‘They’re not, Mr Holmes. Somehow this was left behind in the debris in the experiment store. Without this component, the PDF is useless.’

Just then, Mrs Hudson knocked at entered with a telegram from Lestrade. It was short and to the point. ‘Explosion at Bond Street Jewellers. Figure seen walking through wall. Suspect same as Imperial College incident.’ Holmes turned to Sir James and Challenger, who for once, was speechless. ‘I would suggest, gentlemen, that the owner of this device has made or obtained a replacement’, Holmes opined. This was terrible news. The investigation was back to square one. Holmes left the worst to the last. ‘And by now, whoever it is, knows we’re on their trail’. He scribbled a reply to Lestrade, telling him to put every police division on alert and sent a second telegram to Mycroft summarising this setback. Another council of war was being prepared and I foresaw a long day, and possibly a long night ahead…

The revelation that whoever took the PDF had obtained another focussing coil changed everything. The council of war that took place in the sitting room rapidly dispersed. Mycroft departed for Whitehall. Challenger went with Sir James to Imperial College. Holmes and I remained in Baker Street, while Holmes despatched multiple telegrams, after which we climbed into a hansom and followed Challenger and Sir James to Imperial College. Necessity is the mother of invention and Holmes’ plans had rapidly changed. From our long association I suspected that Holmes was setting a trap, just as he had in the mystery of the Bruce-Partington Plans and so many other adventures.

On arrival at Imperial College, Holmes’ plans unfolded. To all intents and purposes, the campus was unoccupied. The lecture halls and laboratories were empty and silent. Only a single room was in use as Sir James was working late. Five other persons were present but hiding: the hunters and the hunted. Ten o’clock chimed and Sir James laid down his pen and tidied his papers. He turned down the gas in his office and picking out his briefcase, slipped out into the silent corridor. Time passed, very slowly. Holmes and I were concealed just inside the door to the research laboratory. Time passed so slowly, I was starting to imagine this was a dream and I should awake to find myself in Baker Street. However, this was not a dream, as Holmes’ hand on my arm both wakened and warned me to be alert.

From somewhere in the corridor, I heard footsteps. Not confident strides but soft, furtive, footsteps. These could only belong to one person, as I was familiar with Mycroft’s stately tread and Lestrade’s pace. They were the footsteps of our prey. A thrill surged through me, which I rapidly suppressed. This drama had to be played out to its climax, or the exercise would be futile. The footsteps came nearer and slowed, then stopped. Our quarry was outside the very door of the laboratory where Holmes and I were concealed. My hand stole to my pocket, where I had prudently placed my revolver.

I realised this was the tipping-point of our night’s adventure; success or failure was just inches away. Acting too early or too late could be equally disastrous. Suddenly, the footsteps went away, further down the corridor. There was only one place they were going: Sir James’ office. Holmes and I heard the click as the door to the office was shut. Holmes squeezed my arm and together we quietly exited the laboratory and slipped down the corridor. The corridor was dim, but the fanlight in Sir James’ office was the only clue we needed. As Holmes and I approached, we were joined by Mycroft and Challenger, a formidable pincer movement. On a signal from Holmes, we swung the door open and swarmed in. There was nobody there. Holmes clicked his fingers. ‘Anteroom. Quickly’.

Our quarry was there, a shortish sallow-faced man with a thin moustache, clad in a serge suit and carrying a Gladstone bag. Of greater interest was the extraordinary device on the desk, which I presumed was the PDF. It was a glass box, with valves, wires and powered by a device that Challenger later described as an accumulating battery. The business end was, of course, the focussing coil, as our guest rapidly turned in our direction. He spoke in an eastern European accent. ‘What do you want?’. Holmes replied.

‘That device. You can’t have it’. I drew my gun. The man appeared to give up and pushed the PDF across the desk. He slumped against the wall; all the fight went out of him. I put my gun on the table, which was a mistake. Suddenly the man lurched forwards and grabbed the gun and dragged me into the main room. I wasn’t so unprepared however, and applying my knowledge of anatomy, delivered him a hard kick on the shins. The man recovered, however and the cool feel of my gun pressed to my head precluded any further heroics on my part.

The man spoke again. ‘I want that device. You get your friend back when I have it’. Holmes, Mycroft and Challenger shook their heads and glared at the man. He lowered his gun and seeing my chance, I knocked him to the floor. He was still holding the gun, however, so had the better of the argument. Mycroft and Challenger stepped forward, leaving Holmes holding the PDF. Holmes spoke. ‘Mycroft, Norbury’. Mycroft replied, not to Holmes, but to the man.

‘Let Dr Watson go, and you can have your infernal device’. The man turned his head.

‘No tricks’. Mycroft nodded. ‘No tricks’. Mycroft and Challenger stepped aside. I stepped forward, took the PDF from Holmes and handed it to the man, who edged through the office door with his prize and issued a sarcastic parting shot: ‘Thank you, gentlemen. And please don’t follow me, I still have this’ and waved his gun. With an ironic bow, he closed the door, and we heard his receding footsteps. Challenger was the first to react. ‘Come on, we have to get after him’. Holmes smiled and nodded. ‘Yes, we really must’.

Out in the corridor, we saw the figure of our quarry. He could not escape because Lestrade and two constables blocked his exit. The policemen were as formidably large as Mycroft and Challenger; they would have not disgraced any rugby football pack.

The intruder could not leave via the laboratories, because on Holmes’ instructions, Tovey had locked up before our arrival. The man placed the PDF on the floor and taking something from his pocket, screwed it into place and pulled back the heavy switch. There was a rising hum and for a few seconds the corridor was eerily lit. Then Holmes hissed ‘Cover your eyes’ and it was as well for the flash that followed.

A few minutes later, we opened our eyes. Lestrade and his two constables were standing over the remains of the PDF but there was no sign of our prey. ‘He’s escaped again’, Lestrade observed. Holmes shook his head. ‘I think not. I rather think his little device malfunctioned. You could say his scheme has backfired.’ Challenger spoke.

‘How so?’. Holmes shrugged. ‘I took the liberty of rewiring the PDF device. The results were very satisfying’. Suddenly there was a blast of wind, and our little group was knocked off its feet. Mycroft was on the floor, unable to rise. Lestrade and I stepped forward and raised Mycroft, but Holmes was there too. ‘Thank you, gentlemen, but I’ve got this. He’s not heavy – he’s my brother’.

The End