By Brigitte Maroillat

From A Study in Scarlet onward, Sherlock Holmes’s investigations frequently lead him into cases involving foreign elements, placing him repeatedly in international spheres. This comes as no surprise, considering the detective’s background. The French branch of his family includes notable diplomats: Philippe Delaroche-Vernet (1841-1882) and Horace Delaroche-Vernet (1866-1931), who are respectively the grandson and great-grandson of the painter Horace Vernet, Sherlock Holmes’s great-uncle. Moreover, how could Holmes not engage in world affairs with a brother like Mycroft Holmes, who operates clearly in the international arena? Considered a power behind the throne of the British Empire, Mycroft has a comprehensive understanding of international matters without ever leaving his office or club, which serves as a hub of high-level influence.

What gives a consulting detective the legitimacy to intervene, whether officially or unofficially, in international affairs? And what of an amateur venturing into a highly specialized field? At that time, international law was virtually nonexistent, and most matters were handled through diplomacy, which provided Sherlock with openings to either intrude upon or be invited into state affairs. Throughout his adventures, the detective acts as a go-between mandated by foreign sovereigns or governments, or he becomes involuntarily entangled in international plots through private matters, all of which could have serious repercussions on the precarious balance of global relations. This suggests that Sherlock Holmes possesses not only a deep understanding of geopolitics but also a remarkable mastery of languages, one of his many skills.

A Geopolitical Context Conducive to International Intrigues

The international context was increasingly prominent at the end of the 19th century, a time when geopolitics was on the verge of significant transformation with the decline of great empires. Arthur Conan Doyle, a man of his era, immersed himself in the prevailing tensions. For example, in The Naval Treaty, the storyline unfolds within the framework of the Triple Alliance between Italy, Germany, and Austria-Hungary. In this short story, Percy Phelps explains to Holmes and Watson the importance of a secret treaty between England and Italy, which enables England to define its position regarding the Triple Alliance from which it is excluded. Doyle’s narrative illustrates a still-unstable situation where alliances remain fragile. In The Final Problem, Watson revisits this case, underlining its significance and Holmes’s pivotal role in « avoiding serious international complications. »

Similarly, in The Second Stain, Watson describes the context as « the most important international affair » Holmes has ever dealt with. The presence of the Prime Minister and the Secretary of State for European Affairs at Holmes’s residence immediately establishes the crisis atmosphere of this adventure: « All of Europe is an armed camp. » The stolen letter, originating from an unnamed foreign sovereign, poses a threat; if it were made public or reached one of Europe’s high chancelleries, England might be drawn into a world conflict from which victory is uncertain.

Conan Doyle projects the looming prospect of war into his writing, fearfully anticipating a naval attack on Great Britain, an island nation that could be caught off guard. In this context, an enemy submarine offensive would be catastrophic (works like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Captain Nemo’s revenge were critical in shaping technological advancements in hydrofoil propulsion). As early as 1895, in The Plans of Bruce-Partington, Doyle portrays Sherlock Holmes as a crucial player in foreseeing threats from the sea by uncovering plans for advanced submarine technology that would provide England with a strategic advantage in case of conflict. This fixation on the potential for naval defeat not only appears within the Sherlockian canon but is also vividly expressed in the short story Danger!, which depicts an assault on England by a smaller nation deploying submarines. For Doyle, adventure and espionage fiction serve to heighten awareness of imminent threats and encourage preparedness. In this respect, Holmes serves as an exemplary figure. His Last Bow recounts Holmes’s wartime service, depicting him as a true spy in the service of the Crown. Despite his independent nature and reluctance to align with any authority, the detective undertakes international missions when the stakes are high, positioning him as an agent operating at the behest of those in power.

Holmes Officially Investigating in the International Field

Sherlock Holmes often investigates cases where powerful interests are at stake, and, as a result, far from being indifferent to contemporary history, he becomes increasingly involved in solving cases of international scope between 1890 and 1914, a period of heightened geopolitical tensions as a wind of revolt sweeps through the great dynasties of Europe. Thus, a body of short stories linked to foreign policy emerges in the Sherlockian canon. This may seem surprising at first glance, as we would probably not have imagined Holmes so deeply involved in affairs between states. Unlike his brother Mycroft, a loyal servant of the Crown, the detective only pledges allegiance only to logic in the name of justice. This is why he dismisses the formalities of etiquette and deference with the Prince of Bohemia, getting straight to the point. Moreover, Holmes is presented in The Plans of the Bruce-Partington as being interested only in criminal cases and not at all in worldly intrigues. But if he does not disdain occasional forays onto the international stage, it is primarily because of the complexity of these cases, which represent for him more of a challenge worthy of his abilities than a primary interest in international affairs.

A Scandal in Bohemia marks the detective’s first foray into international affairs. When he welcomes Dr. Watson to their former shared apartment one evening in March 1888, Holmes has just received a mysterious anonymous letter, from which he quickly deduces the author’s nationality. Holmes immediately emerges as a very skilled linguist. He will demonstrate this again in The Greek Interpreter : « This young man doesn’t speak a word of Greek. The lady speaks English fairly well. I deduce that she has spent some time in England, but that he hasn’t been to Greece. »

Thanks to his abilities, Sherlock Holmes’s reputation abroad continued to grow. He counted among his acquaintances influential people and high-ranking political and spiritual figures. It is therefore hardly surprising that the detective acquired a stature of high expertise among the crowned heads of his time, as in A Case of Identity, in which Holmes specifies that he received a gift from « the reigning family of Holland » for his services. But monarchs were not his only prestigious clients. Thus, we learn at the beginning of The Final Problem that the French government called upon his services for a mission of great importance. Furthermore, it alludes to the major role played by Holmes in 1894 in the arrest of Huret, the Boulevard assassin. He was rewarded, for services effectively rendered, with an autographed letter from the President of the French Republic and the Knight’s Cross of the Legion of Honor. Similarly, Watson mentions in Black Peter various investigations by Holmes in the year 1895, including that of the sudden death of Cardinal Tosca, a case in which the detective found himself involved at the express request of the Pope himself, which tells a lot about his international renown.

As previously mentioned, Holmes will eventually become more deeply involved in the First World War in His Last Bow. Holmes explains to Watson that for the past two years, since the Prime Minister’s visit, he has infiltrated van Bork’s spy network, using the alias Altamont of Chicago, to feed him false information and hasten his arrest and of other Kaiser’s spies. Actually, Holmes’s extreme involvement is explained by a pressing context and compelling stakes, which also add spice to the mission. The detective is a free spirit by essence. So he distrusts an overly rigid institutional framework where one must constantly answer to others. He prefers to remain in the shadows and play by his own rules, and it is often by chance that he finds himself embroiled in an international affair, through private matters.

Holmes, unofficially consulted in the international field

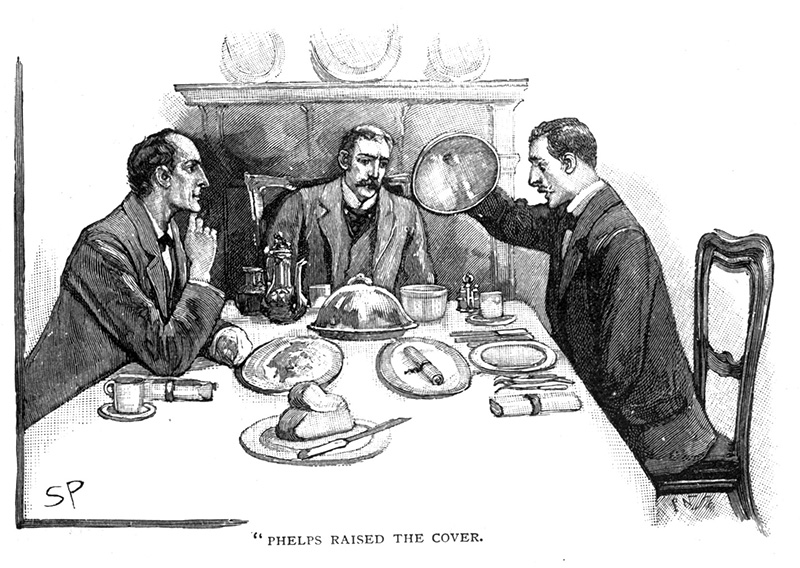

The central position of the Austro-Hungarian Empire crystallized all the geopolitical issues of the late 19th century. Like Budapest in Doyle’s short story The Silver Hatchet, Prague was also the Central European city on which attention was focused. Germany, too. Thus, conspiracies often originated with a character possessing Germanic traits, as in The Engineer’s Thumb. This entire context brought Holmes onto the international stage under the veil of confidentiality, in a case on which he had only been unofficially consulted. The three short stories The Naval Treaty, The Second Stain, and The Plans of the Bruce-Partington perfectly illustrate this. Three espionage stories conceived on the same framework. Each case begins with the theft of a secret document: a secret treaty between England and Italy in The Naval Treaty, a scathing letter from a foreign ruler in The Second Stain, and the plans for a submarine in The Plans of the Bruce-Partington. Furthermore, in all three cases, the theft occurred in the private office or home of those involved. The case has an international dimension due to the nature of the stolen document, but its disappearance stems from a private intrigue, perhaps even a betrayal within the family, as it was stolen by a close relative. These documents are, however, within sight, yet no one notices them. They will not, however, escape the sagacity of the legendary detective. Conan Doyle here cultivates the art of hiding the fundamental, even the extraordinary, within the ordinary, and Sherlock Holmes, the art of masterfully finding the needle in the haystack.

We can also highlight the detective’s remarkable finesse, despite his reputation for being rather as a man with a lack of tact. Holmes effectively salvages the tarnished reputations of those unwittingly implicated in a scheme that conceals the theft. Moreover, he is acting on no one’s orders. Percy Phelps discovers his precious treaty by lifting the lid of a dish, while Trelawney Hope retrieves the famous letter from her private safe as if it had always been there. Like Mycroft, who, by making himself indispensable to the government, sometimes becomes the British government itself, Sherlock here appears as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs itself.

It is for the sheer complexity of the situation that Holmes allows himself to be drawn onto the international stage and engages in skillful manipulation. He outwits the authorities by concealing the truth, which is embarrassing for the victims involved, and he also outwits the spies and blackmailers who hold them in their power : Louis La Rothière, Adolph Meyer, Hugo Oberstein, and Eduardo Lucas. The resolution of cases here is not achieved in the corridors of international diplomacy, but through a perfect knowledge of transportation and communication methods, particularly in The Plans of the Bruce-Partington. Railway networks and the Bradshaw Directory prove far more useful to the detective than the complex intricacies of international networks. There is no mediation by diplomats or high-ranking officials, no games of negotiation here. The threads are unraveled through the use of readily available, yet remarkably effective, methods, much like the pragmatic Holmes himself. But in the international affairs of our time, could there be a place for the sleuth of Baker Street?

Sherlock Holmes in our contemporary international field

In the highly codified world of diplomatic relations that emerged after the Second World War, it would be difficult to imagine Holmes moving with ease. However, it must be acknowledged that in our current era, we allow ourselves more leeway with the codes governing international relations. Alongside some political leaders, people whose profession is neither diplomacy nor politics are also appearing on the world stage, and who interfere in the internal affairs of other countries through short messages on social media. So why couldn’t a mind as astute and independent as Sherlock Holmes’s play a role, without any doubt in a more subtle way? Arbitration and mediation are now preferred methods in both national and international law, when ordinary legal channels struggle to lead to an imminent resolution of conflicts. And from this perspective, we can easily imagine that Sherlock Holmes’s expertise could be highly sought after.