By Brigitte Maroillat

The detective genre has its roots in ancient theater, with early examples present in Sophocles’ « Oedipus Rex, » where Oedipus investigates a « cold case »: the assassination of the King of Thebes. In the end, he discovers that he himself is the murderer, thus creating a plot twist that has inspired many authors throughout history. The detective genre is therefore closely linked to theatricality, and Sherlock Holmes, the ultimate investigative genius created by Conan Doyle, is a product of this connection. He thrives in the spotlight, as the performance itself energizes him more than any accolades he might receive. A fan of surprises and disguises, Holmes adeptly theatricalizes his actions and stages himself, moving seamlessly between the realms of investigation and performance in his adventures. Holmes embodies theatricality in his modus operandi, where his investigations resemble carefully crafted plays. Each detail serves as a clue, and every revelation becomes a dramatic twist. He enjoys captivating those around him, especially Watson, and builds suspense right up to the last moment. When he presents his deductions, he gauges their impact meticulously, observing his interlocutor’s reactions to ascertain whether his argument has resonated. As he admits in The Naval Treaty : « I can never resist a touch of the dramatics. »

Additionally, Holmes’s appearance and mannerisms enhance this theatrical dimension. His signature McFarlane coat, pipe, and deerstalker hat create an instantly recognizable silhouette. Holmes often assumes a role during conversations, alternating between cold detachment and exuberant triumph when he solves a mystery. He masters the art of staging, laying traps, or orchestrating climactic confrontations that resemble scenes from a play. His intelligence is expressed not only through logic but also through his ability to turn investigations into performances. Thus, Sherlock Holmes is inherently a theatrical character, experiencing his investigations as a game in which he is both the director and the actor. Stage actors are often regarded as exceptional interpreters of Sherlock Holmes, as the role requires intensity, precision, and the ability to convey subtle emotions. The skills gained from being a stage actor align perfectly with these requirements: clear diction supports rapid-fire dialogue, and the ability to play on contrasts allows for shifts between frenetic energy and introspective stillness.

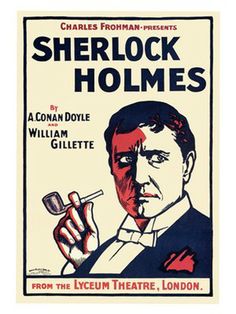

William Gillette, one the first actors to portray Holmes on stage, exemplified this range of acting skills, capturing a unique atmosphere within the Holmesian universe. Gillette stood in contrast to the tragedians of his time, who often indulged in exaggerated theatrics; instead, he employed a nervous yet precise gestural language where no movement was superfluous. This meticulousness allowed his physicality to reflect the workings of an intellectual mechanism in action, serving as a model for later actors like Basil Rathbone, Peter Cushing, Ian Richardson, Jeremy Brett, and Benedict Cumberbatch. It’s worth noting that all the aforementioned actors have backgrounds in theater, and their training in the Shakespearean repertoire is no coincidence. Actors trained in classical theater, particularly in Shakespearean works, can portray the detective with exceptional depth and intensity. They elevate the mastery of language to an art form through their stage presence, psychological complexity, and attention to detail. Shakespeare’s plays require actors to understand the rhythm and musicality of the text, skills that enhance the impact of Holmes’s incisive dialogue and clarity during his deductive monologues. Through Shakespeare, actors learn to explore characters with multiple emotions and ambiguous motivations. This nuanced approach benefits Holmes, who blends cold logic with subtle bursts of humanity. Upon deeper analysis, we see that Holmes is a paradoxical character akin to both Hamlet and Richard III. Each character is deeply introspective, often driven by obsession. In terms of intelligence and strategy, they are characterized by sharp minds and the ability to maneuver effectively to achieve their objectives. Their relationships with drama and mystery are also similar: Hamlet investigates his father’s murder, Holmes solves criminal plots, and Richard III orchestrates them. All three possess a strong stage presence that captivates audiences through eloquent monologues, brilliant deductions, or spectacular manipulations.

Like Hamlet, Sherlock Holmes is on a quest for truth and possesses a sometimes naive and youthful character. This connection may explain why Ian Richardson—who is notably the only actor to have portrayed both Hamlet and Richard III as well as Sherlock Holmes—depicted Holmes as a cheerful and playful character. However, the two characters share more than just a light-hearted demeanor. For instance, both tend towards introspection: Hamlet isolates himself in his monologues, while Holmes retreats into his mind, likening it to an attic where he organizes his knowledge to enhance his reasoning. Their approach to truth is also complex. Hamlet seeks to confirm his uncle’s guilt before taking action, whereas Holmes relentlessly pursues the truth behind every mystery. Furthermore, both characters have a flair for dramatic presentation: Hamlet stages a play to trap Claudius, while Holmes often employs disguises or subterfuge to outwit his adversaries.

In some respects, Holmes also resembles Richard III, possessing dark and unpredictable qualities, as well as being authoritarian, cold, and sardonic. This similarity suggests that the line separating him from Moriarty is quite thin; Moriarty can be seen as a dark counterpart to a Holmes who has succumbed to his darker impulses. Given this context, it’s plausible that Arthur Conan Doyle had Shakespeare in mind when creating the character of Holmes. This connection is particularly notable when considering that one of Holmes’s most famous lines, “The game is afoot,” originates from Shakespeare’s « Henry V. » While this relationship may not be immediately apparent, several authors have explored the links between Doyle and Shakespeare. For example, Robert Fleissner published an in-depth study in 2003 titled « Shakespearean and Other Literary Investigations with the Master Sleuth (and Conan Doyle) Homing in on Holmes, » which outlines various correlations between the two. Other writers have also drawn parallels, such as Vincent Starrett in « The Unique Hamlet, » and Barry Day in « Sherlock Holmes and the Shakespeare Globe Murders, » as well as Barry Grant in “Sherlock Holmes and the Shakespeare Letter,” which involves Holmes searching for a stolen letter supposedly written by Shakespeare. The playwright from Stratford-upon-Avon has always influenced Anglo-Saxon writers, whether consciously or unconsciously. Sir John Gielgud once remarked, “Shakespeare is in everything; it is impossible to escape his prodigious power of attraction.” In the Sherlockian canon, the art of incisive dialogue, the crafting of mysteries, and the exploration of human motivations are all part of a literary tradition that is partially an inheritance from Shakespeare. Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective has captivated audiences since the publication of his novels over a century ago, continuing to inspire novelists and playwrights alike. Holmes’s charisma is rooted in his consistent self-presentation. Between his impressive appearances, calculated silences, and penchant for dramatizing investigations, he transforms each inquiry into a performance. Thus, Holmes transcends the role of a mere detective and becomes an actor in his own legend, manifesting as a hero perfectly suited for the stage, where his genius, uniqueness, and dramatic presence can truly shine.