Nicholas Meyer was kind enough to grant us an interview on his return from New York where he attended the BSI dinner. As usual, the Holmesian scholar enthusiastically lent himself to the questioning game. As a music lover, he also shared his passion for opera with us. The Shakespearean dimension of Moriarty and his similarity to Baron Scarpia in the Puccinian opera Tosca, clearly tickled his imagination and seemed to have sparked his reflection. Interview conducted By Brigitte Maroillat

La Gazette du 221B : First of all, what could we wish you for the new year ? What are your expectations for 2025 ?

Nicholas Meyer : I suppose my expectation is that somehow we survive President Donald Trump…

G221B : As you know, I got caught up into your latest novel. I love the idea of an older Sherlock Holmes who travels to Boston and then Mexico to prevent the Allies losing World War I by involving America in the conflict. It is captivating and superbly executed. How this story originate ?

N.M: Well, I never quite know where ideas come from. They pop like Athena from the head of Zeus, but I don’t know who is Zeus? I read a lot of history. I read a lot of biography. And maybe this began about 4 years ago, when this book was published…Hang on one second. (He gets up to take a book from the shelf behind him. He sits back down and shows me the book he’s holding) This one, The Zimmerman Telegram: intelligence, diplomacy, and America Entry into World War I by Thomas Boghardt. This is the second book with this title! The other one, with the same titIe, I read in my twenties. It was written by the American historian, Barbara Tuchman. Then, when this new one came out, I read it too (he leaves through Boghardt’s book). It was published. 2012. And it’s such a crazy story, the whole Zimmerman telegram. And somehow, I got the notion in my head of Sherlock Holmes being involved with this. It seemed like such a cool idea. I need time to write a book and I played with this one for another 5 years! Sort of forgetting about it and then coming back to it; it was a tricky book to write. Harder than some of the other ones. Because It demanded that I convey to readers who don’t know anything about this event, and also who don’t know anything about the last Sherlock Holmes story, His last Bow. It wasn’t so easy, but nobody said it was supposed to be easy, anyway.

G221B : Does it mean this novel is the continuation you dreamt of writing to His Last Bow?

N.M : Yes, yes, it is a kind of a continuation of His last Bow in which we learn that in the run up to the war, Holmes was undercover in America.

G221B : You plunge Sherlock Holmes into a world that is similar to our own, where alliances, treaties, and human betrayals threaten to create another cataclysm. Were you inspired by our times to write this story?

N.M : That’s a very interesting question. I have maintained elsewhere that all works of art are products of the times in which they are created. Mozart doesn’t just sound like Mozart. He sounds like late 18th century middle European music. Renoir does not just look like Renoir; he looks like late 19th century French Impressionism. Say I were to show you five movies, all set in 1789. One movie was made in 1920; one in 1950. Another was made in 1990. And so on. You would be able to tell within five minutes and five years when each of these movies was made, because they would inevitably reflect la mise en scene (in French). When you know what ideas were in prevalence, what fashion, how the eyelashes were worn, and so on, you can date each one. So whether I was consciously thinking about the world that I inhabited when I wrote The Telegram from Hell, I think it’s fair to say those things were on my mind, whether I was totally aware of it or not. And occasionally, when you’re writing, you say : « Oh, this is kind of cool, because it makes people think of X Y or Z. And you don’t have to spell it out for them. They’ll figure it out. They’ll recognize it »

G221B : Holmes and Watson visit different places, including Mexico. You have already made a movie in Mexico, and I imagine it helps you to share so accurately the atmosphere of the city at a specific time of its history, after Porfirio Diaz had made it a kind of Little Paris.

N.M : Absolutely. I had been to Mexico in 1984, when I was making that a movie called Volunteers with Tom Hanks, but I had not been back since. I had reached the point in writing the novel where Holmes and Watson find themselves obliged to visit Mexico City. With all the research that I was doing, I said to my girlfriend, « I think we have to go because I’m not feeling comfortable writing about this place after all these years » I had some contacts. This was from the movie business. So, we went and made what we would call when we prepare a movie, « a location Scout ». We looked at all the things. I was very interested in The Western Union telegraph office in Mexico City. I had no idea that it was a museum, and that there was even an exhibit about the Zimmerman telegram! The telegraph office was built by Diaz, as were many public buildings in Mexico City. The telegraph office looks rather like a palace, with murals on the ceiling. Like Versailles! It’s just unbelievable. Yes, Diaz wanted Mexico City to look like Paris.

G221B : You mix historical characters with fictional ones. How does that work so well and sound highly credible?

N.M : Questions like these are very hard to answer because I’ve asked the same questions about other artists that I admire. So how I do this? I must say I don’t know. I don’t know how I do things. Socrates was told by the oracle at Delphi that he was the wisest man in Greece. And he thought, « Oh, that that can’t be right, so I must find someone wiser than I », and he goes talking to all of Greek society, and finally he gets to the poets. I think he means the artists, the painters, the sculptors, the whatever, who are, of course, all men. And he thinks : « These men who create so insightfully about the human condition will prove to be wiser than me », and he says, « Imagine my surprise when I found that artists were the stupidest people that I spoke to ». They were like « comme les enfants » (in French). Except when they did their art and they go into a kind of trance, and in the trance, they take dictation from God. And this they call “inspiration”! And when they come out of the trance, they don’t know where the hell they’ve been, and they go back to being sort of children again and they cannot explain anything they did while in their trance. And I cannot explain how, when I sit at my desk desk, or with a pad on my lap and start to write, I know how Alice Roosevelt talks or Sir William Melville talks. It kind of comes to you! And if you do it right, then people don’t question it. If you do it wrong, people go : « Humm, this doesn’t feel « à la verité » » (in French)

G221B : I know you don’t like most of Sherlockian movies because Watson is portrayed as an idiot. And indeed, it would be unbelievable that a genius could be friend with a jerk. So, in your novels, you seem to develop a lot Watson who becomes as active in its own way as the great detective himself. Is this your way of enhancing the image of the character?

N.M : You spotted it! Yes, from my first novel, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, I was trying to correct this simplification of Watson. Because, as you point out, why would a genius want to team up with such a silly person? I think that partnership in a way can be traced to Don Quichotte. Watson’s like Sancho Panza. Sancho is not an idiot. He is a sort of “realist”, who, as he says, knows which side of the bread has the butter on it. He understands, Quichotte’s “eccentricities”, but also, he loves being with Don Quichotte and having Don Quichotte explain things to him. I think Watson is also like that.

G221B : You usually said people confuse heroes with gods. At the beginning of the book Sherlock Holmes appears at Watson’s home with a black eye, a missing tooth and a cracked rib. Is it your way to make Sherlock more human and less invincible ?

N.M : I don’t think that was on my mind. What was on my mind was getting the story underway, and as the story unfolds and Holmes explains to Watson why he’s in such bad shape. I don’t believe, when I wrote it, that I was thinking about trying to emphasize the mortality, the vulnerability of Holmes. This topic came about when The Seven-Per-Cent Solution was written. Some afficionados were very distressed by Holmes’ addiction to cocaine because they had, I think, elevated their hero into the status of some kind of superman, and therefore he could not have feet of clay. He could not be mortal, he could not be vulnerable, he could not be human. And so they argue that he wasn’t really an addict. He was kidding Dr. Watson. He was teasing the gullible doctor, whatever, which all seems wrong or silly. I don’t think heroes need defending because they turn out to be human. They’re more real. It seems to me they are more real if they have problems like everybody else, whether it’s drug addiction or they’re alcoholics. They turn out to be just ordinary people with extraordinary gifts. At the end of the day, genius is inexplicable. We cannot explain Mozart’s genius. But it’s also true that if you read the letters of Mozart with all their scatological references and silly sign offs, you will wonder How can somebody who writes such nonsense create such music? And it’s the same problem, I think, that people have with Holmes. How can somebody so brilliant and wonderful and humane turn out to be shooting up? Put this another way: if a man jumps into a river to save a drowning child, we can all agree: he has performed a heroic act. But if the same man jumps into this same river to save the same child, and does it with an anchor attached to his leg, or a ball and a chain? Is he more of a hero or less? I think that the fact that Holmes functions with the ball and chain of his addiction makes him more heroic, but doesn’t make him a god. He’s not a god. That’s the whole point.

G221B : You often refer to music and opera all the time in your novels. And in The Telegram from Hell, it’s a kind of « clin d’œil » to your readers who are opera lovers, because they know immediately the character, who pretends to be an opera singer, is lying. You have a passion for Opera. What a Sherlockian Opera could be in Nicholas Meyer’s mind? And would you like to stage an Opera production?

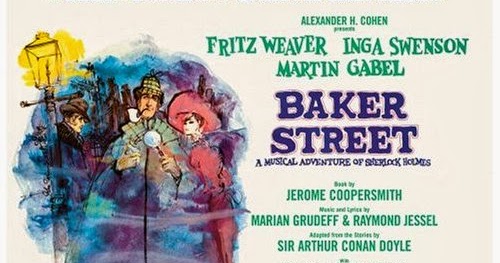

N.M : I have a recording of music written for a Sherlock Holmes ballet. It’s not called Sherlock Holmes, I guess, for copyright reasons, but The Great Detective. I’ve never seen the ballet, but would love to! And it would be very interesting to have a Sherlock Holmes opera. I wonder what it would be like in music with Holmes figuring out the clues. And you know, there’s some wonderful duets for men in opera and also you know that everybody loves the duet from Bizet’s Pearl Fishers (Nb : Les Pêcheurs de perles). So, Holmes and Watson could be a great opera duo; it’s interesting that nobody has tried it, though there was a Sherlock Holmes musical, BAKER STREET, on Broadway. It was not that successful.

G221B : Or maybe a musical…it would be a great idea. ?

N.M : Yes, it is ! Actually, I was approached years ago to make a musical of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. But I sort of didn’t know how to do it. And so, it didn’t go anywhere. Too bad. I just couldn’t figure it out. But maybe if I was not bound by that book and that particular story… And it would have been to involve Doyle as a character! But I don’t think Doyle either knew or cared very much about Holmes’ music abilities. It was just meant a sign of his sort of Bohemianism. His artistic nature. I think Doyle never took these things as seriously as I did. I come from a musical family, a family of musicians. So music is a passion of mine, not just opera. So I developed that idea a little more than Doyle did. (Incidentally, Doyle did try to write an opera with J. M. Barrie – author of Peter Pan – but it was not a success).

G221B : I know you have great memories of Sir Laurence Olivier as Moriarty in the movie based on your novel The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. it was indeed a perfect cast choice because there is something Shakespearean in the character of Moriarty. Would you like to write a story with Moriarty as main character?

N.M : Well, first of all, thank you for the suggestion. I have to think about. But how do I explain this? For me, Moriarty is a creation of Holmes’ cocaine-induced the paranoia, but he’s not entirely wrong when we learn that Moriarty carried on an affair with Holmes’s mother and that the father shot the mother and Moriarty escaped. Actually, he was a math tutor. He was not “the Napoleon of crime”, except in Holmes’ mind, but when we learn of his adultery with Holmes’s mother, he wasn’t so wrong, after all.

G221B : Let’s get back to the opera. Don’t you think there’s something similar between The Empty House and the third act of Tosca? Moriarty and Scarpia seek revenge by proxy beyond their death. I think you could write something fascinating about the character as a Sherlockian and an opera lover.

N.M : Very good suggestion! I had not until this instant thought of him as a version of Scarpia. And it’s very interesting. I have to think about your idea. I’m a very slow thinker. I’m a very slow reader. I’m a very slow in everything, but I will think about it. « Merci» ! (In French)