By Brigitte Maroillat

While Sherlockian authors have written extensively about Sherlock Holmes and music, they have been less forthcoming about him and opera, except through the character of Irene Adler, a contralto singer who was the opera star of the Warsaw Imperial Opera House before she left the stage. Beyond studies relating to the strange and fascinating bond the detective has with Irene, the adventuress of all stages, theatrical and non-theatrical, lyric art has been somewhat overlooked, even though it is undeniably present in the canon. And if views have not immediately focused on Opera in Holmes’ life, it is undoubtedly because the equation is inherently contradictory. How could such a cerebral being, who gauges every dangerous emotion along the path of the intellectual process, have such an attraction to this art and its human passions, often brought to their paroxysms? Music, which relates to mathematics, seems to match every way to Sherlockian logic. However, opera, which often has only the heart as its reason, is not exactly the shore to which we would expect to see the Baker Street bloodhound moored. This delightful addiction, among other more unfortunate ones, deserves analysis.

Symphonic music is for Holmes a way to regenerate after a significant mental effort, as in The League of Red Heads where he says to Watson, “We know quite enough. Let’s leave room for pleasure. Sarasate is performing at Saint James Hall soon. We fly to lands where music, poetry, and harmony reign.” Moreover, it is paradoxical to note that Watson, who nevertheless presents Holmes as a pure thinking machine, uses a whole range of emotional shades to describe Sherlock’s state of mind when listening to Sarasate. But what about opera? Does lyrical art mean to the detective the same avowed and assumed pleasure that he has for music? Does Opera have the same attraction for the detective who intends to keep a cool head?

Actually, the way Watson describes Holmes’s posture at the Sarasate concert suggests, the detective is not as devoid of emotion as we might initially imagine. On the contrary, the detective knows he is sensitive to them, and he is wary of them. This is why he carefully avoids any outpouring of emotion and passion. This perhaps explains why he is more attracted to German music, and therefore German opera, than to Italian opera. “German music is introspective,” he tells Watson in The Red-headed League, and this better suits his personality and inner way of thinking. Holmes is therefore selective when it comes to music, and the same is true of opera. And we understand then that his preference goes to great works inspired by history (Meyerbeer) or mythology (Wagner) rather than to an Italian repertoire that is too expressive and emotionally demonstrative. He is undoubtedly a knowledgeable opera lover, and not an occasionally curious listener. If we are to believe what he says to Watson in the conclusion of The Hound of the Baskervilles, he does not hesitate to rent a box to fully enjoy Opera work. In this case Les Huguenots, a great French opera, a historical drama set against the backdrop of a religious war between Protestants and Catholics, which is not without resonance with a historical novel by Conan Doyle: The Refugee, A Tale of Two Continents. It goes without saying that Conan Doyle, deeply immersed in the culture of his time and an author passionate about history, could not ignore the existence of Meyerbeer’s work. Moreover, he also refers to it in A Scandal in Bohemia in which it is clearly mentioned that Irene Adler, who played many male roles on stage (which also allows her to play a trick on Holmes) played Urbain in Les Huguenots. This great opera by Meyerbeer is a common thread in the canon between Holmes, Irene Adler and the author Conan Doyle.

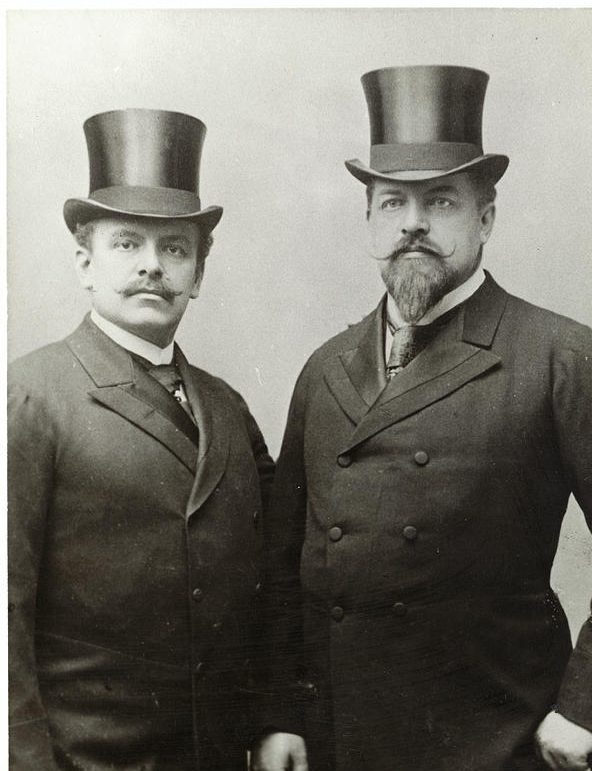

It is interesting to note that when Holmes speaks of French opera, he is primarily referring to the performers and their techniques, not to the composer or music. In this regard, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Holmes mentions the De Reszke brothers, Jean, a dramatic tenor, and Edouard, a bass, who performed Les Huguenots together several times between 1880 and 1890 all over Europe. Similarly, for the music, Holmes also focuses on the specificities of Neruda and Sarasate’s approach or Joachim’s fingering in Beethoven’s violin concerto, which he recalls with emotion at the beginning of The Red-headed League. On the other hand, German opera, in his words, often seems to be summed up by the name its composer: Wagner. “By the way, it’s not yet eight o’clock, and they’re playing Wagner at Covent Garden!” If we hurry, we can arrive in time for the second act,” implying here that only the composer makes the operatic work’s value. Holmes therefore seems to be primarily interested in performance technique and musical composition, not in opera’s story itself and the bouquet of emotions it contends, which seems to him merely anecdotal.

His keen interest in technique applied to music leads him to use, for the purposes of his investigation, a cylinder recording in The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone, which demonstrates here a meticulous knowledge of all the modern technologies of his time. Moreover, this is not just any recording: he recorded himself playing the Barcarolle from Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann. A choice of operatic piece that might seem surprising here, given the poetic and romantic soul of such an aria, the polar opposite of Holmes’s personality. Could the detective be a romantic at heart? Not so… because this choice is easily explained from both the detective’s and the story’s point of view: “Belle nuit, O nuit d’amour” is a haunting melody, almost an ostinato, easily identifiable and readily associated in the collective unconscious with a live musical performance, which reinforces the illusion that he is actually performing in the room. It also creates a somewhat hypnotic atmosphere. With this melody, Holmes knows he can entertain his adversaries’ attention to the music, rather than to what he does. Holmes here draws on his musical knowledge to use it as a psychological asset in his investigation.

Holmes’s interest in opera is in tune with a deep artistic sensibility that undoubtedly comes from the French branch of his family. Even if its intense dramas contrast with Holmes’s methodical and rational personality, opera nonetheless connects with a part of himself. It offers him an emotional outlet, a diversion that allows him to reconnect with the heart and soul he excluded from his mental universe out of necessity and distrust. It is also a way for him to return to the “Woman”, Irene Adler, whose voluptuous song he enveloped himself in, for a fleeting moment in Scandal in Bohemia. But there again, he only lets himself go to the emotion of a voice, under the trappings of a hideous groom, as if to protect himself, a comfortable disguise for one who flees emotions in all their aspects. Insensitive no, prudent yes. He voluntarily allows himself to stand on the edge of the dizzying cliff of emotion without ever plunging into it. It is also astonishing for someone whose life could be a great plot for an opera. Let us imagine Holmes as a lyric-spinto tenor, and the infamous Moriarty as a Verdian-type bass, because the hero’s enemy always has a vocal instrument in dark range. Yes, that would be very stylish.